Metaverses – Players and Spaces

Note this is an excerpt from my masters dissertation An Inquiry into Designing Metaverses (2021), this is a study into designing and creating multiplayer virtual worlds and connecting those worlds into a wider virtual universe known as a metaverse. Melonking.net hosts a number of these excerpts broken into sections of particular interests. You can find all sections here or feel free to contact me if you would like a copy of the entire original document.

What are Players?

Players are the real people inhabiting and interacting with a virtual world. There are a number of steps that make up the connection between a player’s human self and their presence in the virtual world: the human, the computer, the programme, their avatar, and the world.

There is no guarantee that a player is a single person. A player account accessing a virtual world could be accessed and operated by many people. A player and an individual may be quite different things (Dibbell, 1994).

All these steps play a role in the player’s sense of ‘embodiment’ within the virtual world. Embodiment is their sense of presence, their physicality within the virtual world. That sense is the product of the player physically interacting with their computer, the physics that define the virtual world, the visual appearance of their avatar, and the player’s own personality creating a story for their avatar.

There is a feedback loop between the player and their avatar — the player defines the avatar but the avatar also defines the player. This is discussed in The Social Life of Avatars where Frank Biocca describes a physical body, a virtual body, and a phenomenal body, the phenomenal body being the individual’s mental representation of their body (T.L. Taylor, 2002). In their argument, the phenomenal body is warped away from the physical by the existence of the virtual.

This description could be considered a little biased towards physical representation. A person’s identity can exist quite separately from any physical form. Biocca’s phenomenal body could be regarded instead as inner identity. This identity is formed from all personal experiences in reality, from media and dreams to virtual worlds. A person is both actively constructing their identity as well as being constructed unwillingly by events in their life.

This raises interesting philosophical debates. If a person’s identity is formed by the sum of their life experiences, including virtual experiences, is it right for the developer of a virtual world to dictate what those experiences should be? In the physical world most societies have laws, but those laws can be broken. Virtual worlds have laws too, however, unlike reality, the virtual laws are built into the structure of the world. Laws can become physics. Should players have the right to break laws in a virtual world? (Dibbell, 1994)

There is also a distinction between players and developers. Traditionally, a developer is a person who makes the game or virtual world, and a player is a person who accesses that game. Increasingly the line between these two has become blurred. A player may become a partial developer by creating player-generated content. Equally, many developers play the games they are developing, which poses the question, is all content player-generated? The simplest definition is that a developer is the person who defines the structure of the world, while a player is operating within the bounds of that structure.

What is Player-generated Content?

One feature of both virtual worlds and metaverses is player-generated content. This refers to the player’s ability to create content within a virtual world. This content can be anything including, but not limited to, text, 3D models, sounds, images, or gameplay. Player-generated content is not supplied by the developer of the virtual world; however, the developer may provide tools to help the player create this content.

To understand player-generated content, let’s look at the World Wide Web, the most ubiquitous space of player-generated content available. In the context of the web the term ‘user’ is more common in place of player. However, player will be used here for the sake of consistency with virtual worlds. Primarily, the web is an interconnected platform for sharing information and for many people it has become a platform of self-definition. Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) on which the web operates, defined it as “a collaborative medium, a place where we all meet and read and write” (Berners-Lee, 2005).

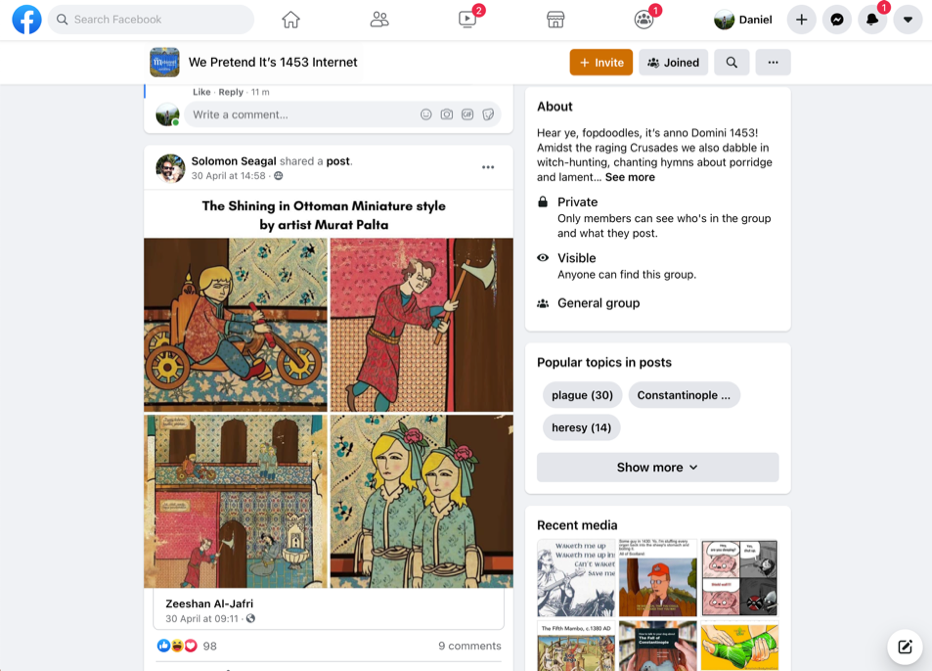

Silver’s article for Forbes Magazine, “What is Web 3.0?” is a discussion about the future development of the web. It describes a common narrative: the early web was difficult to use and only a small number of developers could create content on it; the web today offers more freedom, as players can upload content and become creators; the web tomorrow will be nothing but player-created content (Silver, 2020). Figure 5 illustrates Silver’s vision of the web today, with freely uploaded content; however, this content must conform to a predefined structure which the player does not have the freedom to modify.

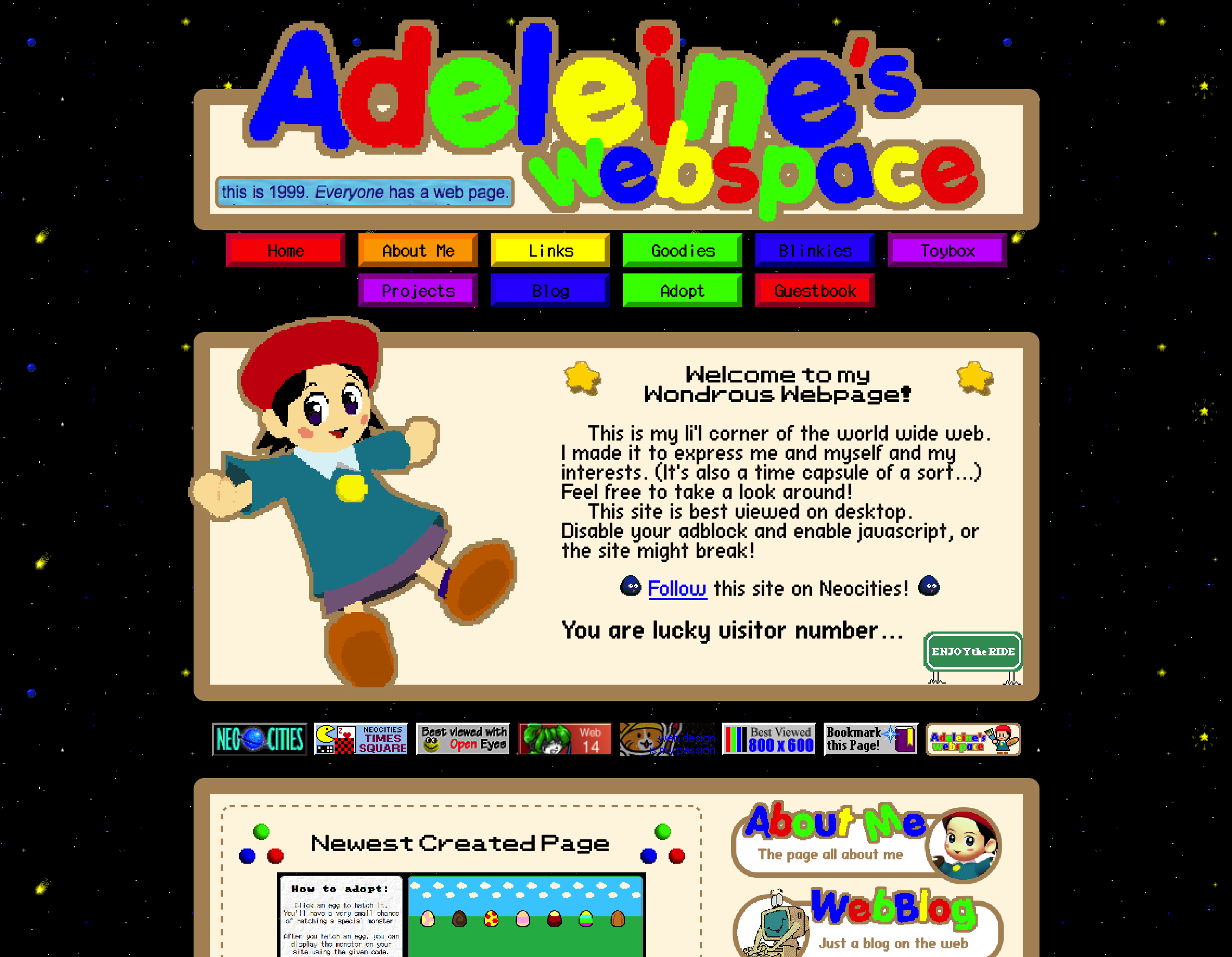

Olia Lialina presents an alternative and inverse history in her article “From My to Me”. She talks about freeform early web development, where players created their own websites from scratch. She goes on to describe a partial loss of freedom as player uploads became standardised by structures in the social media age. Finally, she theorises that the Web 3.0 era could be characterised by a total loss of player freedom, being populated only by content provided within developer-made structures (Lialina, 2021). Figure 6 shows a modern interpretation of Lialina’s freeform early web, which is in direct contrast to figure 5. There is a distinct conceptual and asthetic diffrence between these two web spaces.

Figure 1 shows the Facebook group “We Pretend It’s 1453 Internet”. There is a focus on content provided by many people, while the structure is provided by Facebook. The culture of this group can only be expressed through members’ content, which contrasts with the structure.

Figure 2 shows dokodemo.neocities.org in April 2021, a modern website made in the fashion of an old site. This site is a combination of its content and its structure, both working together to create its aesthetic. This is the work of one individual without formal web development training.

The truth between these two histories may be somewhere in the middle; however, the comparison raises key questions about player-generated content. How ‘player-generated’ is that content? How regulated is it? How regulated are the tools used to make it? What does creating, uploading, and sharing of player content mean to the players and the platform? How do the players associate themselves with this content in this scenario? How does the website or structure that holds this content also define the content and the player?

In the case of the web today, there is significant backlash against platform-regulated player content. This can be because of privacy, or for political or other reasons. Perhaps more interesting to our discussion is the backlash against platform-provided structures. A structure, in this case, is the way the content is held and displayed for the player. Facebook is an example of a rigid structure where the player has little ability to modify the appearance or interaction of the Facebook site. The player can only control what content is on display, within Facebook’s rigid structure.

What is Structure?

In the previous section, Facebook was described as a structure. When discussing virtual worlds, we are primarily discussing the structure of the virtual world. If a virtual world had no structure, it would be an imaginary world. There is a distinction between content and structure.

Structure goes beyond the visible parts of a virtual world; it refers to the world’s interface but also the underlying technology that supports it. Structure allows the virtual world to exist. Structure also defines the final experience that world will provide and the kind of communities that will form within it. For example, if the underlying technology of a social network does not allow you to upload images, that changes the nature of the experience.

Rather than focus on technical structures alone, let’s take a moment to consider a real-world physical structure. An art gallery is analogous to a virtual world — it’s a definable structure that primarily exists to be populated with player-generated content, the artworks. In his collection of essays Inside the white cube, published in 1976, Brian O’Doherty questioned the idea of the ‘white cube’ art gallery. This is the concept that an art gallery should be a neutral and somewhat standardised space. This is beneficial to the gallery as it means artworks can be moved between different rooms and displayed in a standard way.

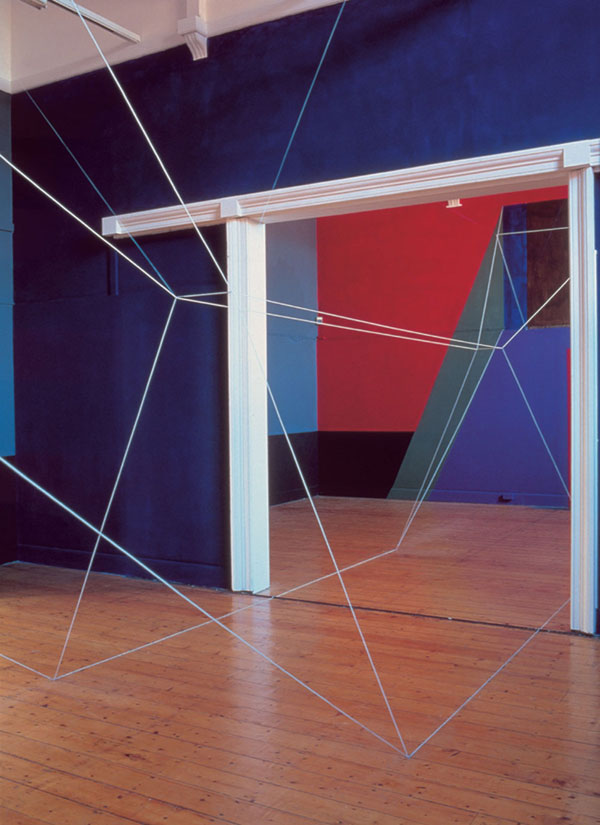

O’Doherty’s argument was that this process is not neutral; isolating the artworks from the gallery’s structure influences and defines what kind of art will be created and promoted (O’Doherty, 1999). O’Doherty attempted to challenge this idea by creating works that included their structure. Figure 7 is an example of this, showing an artwork that is within the room, but which is also the room. The artwork can only fully function when viewed within this structure.

Figure 3 shows Borromini's Corridor, Rope Drawing # 103 from 1995 by Brian O’Doherty, at the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork.

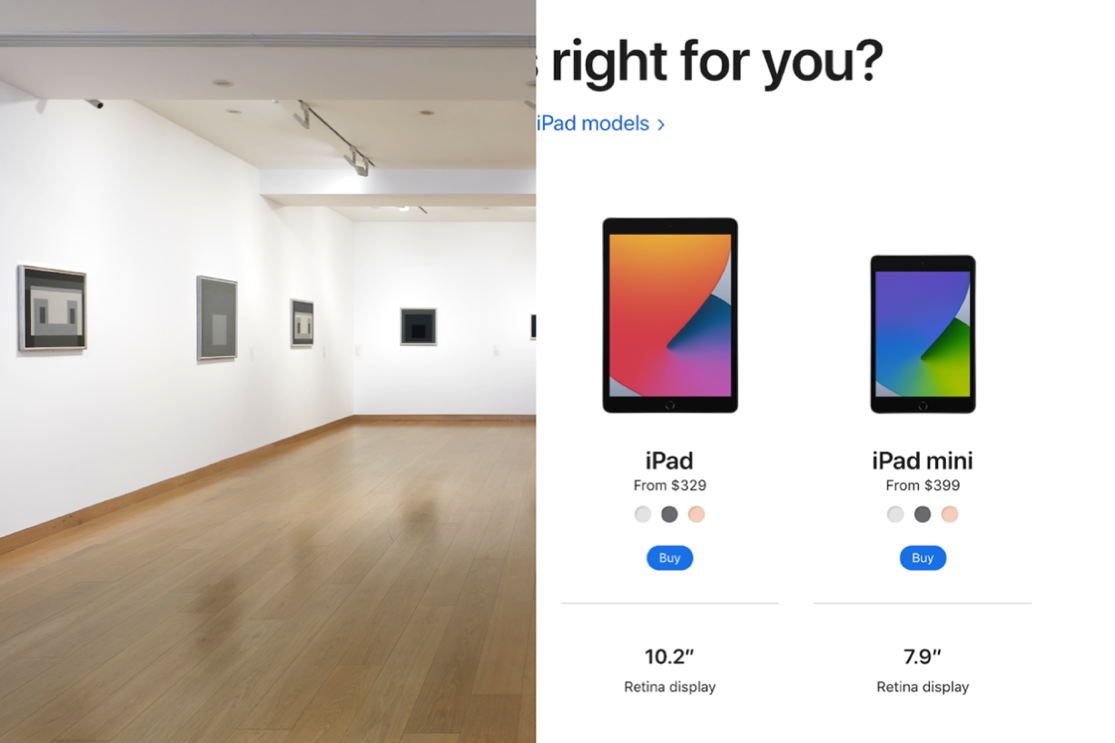

In computer interface design we see a similar philosophy. Modern websites tend to be white cubes. The prevailing view is that the interface should be invisible, leaving only the content. Even the word ‘interface’ is often replaced with ‘experience’; UI is changed to UX (Lialina, 2012). However, like O’Doherty’s white cube gallery, such invisibility influences the content — it is not invisible. This is illustrated in figure 8 where both structures shown have an implied consumer focus. The structure has been made invisible to showcase the content: without structure the content becomes a defined product.

Figure 4 shows a white cube gallery on the left and a white cube UI on the right from apple.ie.

The article “Beyond the White Cube”, by Oliver Jameson, brings O’Doherty’s ideas up to date and applies them to virtual worlds. Jameson talks about virtual worlds as artworks, and as tools for the artist to gain control of the structure within which their art exists (Jameson, 2020). An important conclusion is that the virtual world becomes the artwork, the structure becomes the content. The two cannot be separately defined. We will see later that this has implications for any economy in a virtual world. This also suggests that for a virtual world to be fully realised the player must feel they have as much ownership over the structure of the world as the content within it.

Berners-Lee, T. (2005). Weaving a Semantic Web. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.uaa.alaska.edu/afef/weaving the web-tim_bernerslee.htm

Dibbell, J. (1994). A rape in cyberspace or how an evil clown, a Haitian trickster spirit, two wizards, and a cast of dozens turned a database into a society. Ann. Surv. Am. L., 471. Retrieved from http://www.juliandibbell.com/articles/a-rape-in-cyberspace/

Jameson, O. (2020). Beyond The White Cube. PLAYSTYLE. Retrieved from https://playstyle.world/Beyond-the-White-Cube-The-Virtual-Gallery-Space

Lialina, O. (2012). Turing Complete User. Contemporary Home Computing, 14. Retrieved from http://contemporary-home-computing.org/turing-complete-user/

Lialina, O. (2021). From My to Me. In Turing Complete User. Resisting Alienation in Human-Computer-Interaction. Retrieved from https://interfacecritique.net/book/olia-lialina-from-my-to-me

O’Doherty, B. (1999). Inside the white cube: the ideology of the gallery space. Univ of California Press.

Silver, C. (2020, January 6). What Is Web 3.0? Forbs. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2020/01/06/what-is-web-3-0/

T.L. Taylor. (2002). Chapter 3 Living Digitally: Embodiment in Virtual Worlds. In The Social Life of Avatars.